Mystras - a walk into the past (overview)

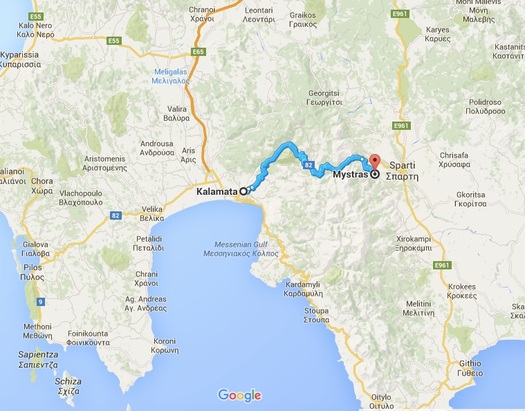

Kalamata to Mystras is only 58 kilometers, but the trip across the Taygetos mountains is dramatic and breathtaking. We cross rivers, glimpse deep gorges and ravines, ride curving mountain passes and see cypress, pine, oaks, wild olive trees, Greek fir and Black pines. The Taygetos mountains also have a wide variety of birds and over 100 plant species, many It is a popular destination for climbers and its orange trees produce a unique honey. Not surprisingly there are dozens of species of butterflies in this area. (See the image of the Taygetos Blue Butterflly in the gallery below)

In 1204 soldiers of the Fourth Crusade conquered Constantinople and the political preeminence of Byzantium began to decline. These events also sealed the schism between Eastern and Western Christianity as Byzantine and Western forces battled over various regions in the East. In the Peleponnese the Franks established dominance by 1210. In 1249 Prince William I Villehardoin built a Frankish palace in what was to become known as Mystras.

Historians don't know much about Mystras before the Franks arrived. While archaeologists have found a few ancient relics, they did not uncover walls or building sites before Villehardoin built his castle. Manolis Chatzidakis in his book "Mystra: THe Medieval city and the Castle" says that the building materials used to construct the houses, walls and castle and other buildings came from nearby Sparta. The Franks and Byzantines continued to battle for hegemony of the Peloponnese and it was for this reason that Villehardoin built the castle and its fortification to hold off the Byzantine armies. He was assisted by the Venetians, but his dominance lasted only 12 years. In 1261 the Franks gave up Mystras to the Byzantine Empire in exchange for the captured Villehardoin. Emperor Michael VIII Paleologus made Mystras the seat of the Despotate of Morea and from then Mystras began to flourish.

It was the defeat byf the Franks that allowed all of the Peleponnese, and particularly Mystras, to become, in effect the center of Byzantium outside of Constantinople since the Eastern empire was holding off the Ottomans. Mystras became both a political and ecclesiastical seat. Chaatzidakis points out that by the end of the 13th century the village of Mystras had become a city. Internicine conflicts amongst Byzantine families kept the region unstable, and Mystras was often an outpost refuge for disputes over who should rule in Constantinople. By 1460 the Ottomans were in control of the region and the glorious and creative political and ecclesiastical growth of Mystras began to fade. But during the period when Mystras became the second most important center of Byzantium it attracted scholars, philosophers, architects, painters, artisans and prelates. Mystras was a center of Byzantine growth.

Historian Sir Steven Runciman describes the visual splendor of one's first glimpse of Mystras:

In 1204 soldiers of the Fourth Crusade conquered Constantinople and the political preeminence of Byzantium began to decline. These events also sealed the schism between Eastern and Western Christianity as Byzantine and Western forces battled over various regions in the East. In the Peleponnese the Franks established dominance by 1210. In 1249 Prince William I Villehardoin built a Frankish palace in what was to become known as Mystras.

Historians don't know much about Mystras before the Franks arrived. While archaeologists have found a few ancient relics, they did not uncover walls or building sites before Villehardoin built his castle. Manolis Chatzidakis in his book "Mystra: THe Medieval city and the Castle" says that the building materials used to construct the houses, walls and castle and other buildings came from nearby Sparta. The Franks and Byzantines continued to battle for hegemony of the Peloponnese and it was for this reason that Villehardoin built the castle and its fortification to hold off the Byzantine armies. He was assisted by the Venetians, but his dominance lasted only 12 years. In 1261 the Franks gave up Mystras to the Byzantine Empire in exchange for the captured Villehardoin. Emperor Michael VIII Paleologus made Mystras the seat of the Despotate of Morea and from then Mystras began to flourish.

It was the defeat byf the Franks that allowed all of the Peleponnese, and particularly Mystras, to become, in effect the center of Byzantium outside of Constantinople since the Eastern empire was holding off the Ottomans. Mystras became both a political and ecclesiastical seat. Chaatzidakis points out that by the end of the 13th century the village of Mystras had become a city. Internicine conflicts amongst Byzantine families kept the region unstable, and Mystras was often an outpost refuge for disputes over who should rule in Constantinople. By 1460 the Ottomans were in control of the region and the glorious and creative political and ecclesiastical growth of Mystras began to fade. But during the period when Mystras became the second most important center of Byzantium it attracted scholars, philosophers, architects, painters, artisans and prelates. Mystras was a center of Byzantine growth.

Historian Sir Steven Runciman describes the visual splendor of one's first glimpse of Mystras:

|

|

|

"Travellers who take the main road that ran from Tegea in ancient days and runs from Tripolis today, climb up over the spurs of the Parnon range; and suddenly, as they go round a hairpin bend, wit the Spartan mountain citadel of Selassia, the guardian of hte pass, high above them to the east, there lies below them a valley lush with olive-trees and fruit-trees, witt the River Eurotas winding between oleanders and cypresses, and behind the valley, rising steep from the plain, the sternest and most savage of all Greek mountain ranges, Targets, with its five peaks, the Five Fingers, covered with snow till late into the summer. In front of the mountain wall, if the morning sun is shining, they will notice a conical hill, dotted with buildings and crowned by a castle. This is Mistra." (Steven Ranciman, The Lost Capital of Byzantium: The History of Mistra - a reissue of Mistra: Byzantine Capital of the Peloponnese, 1980)

|

|

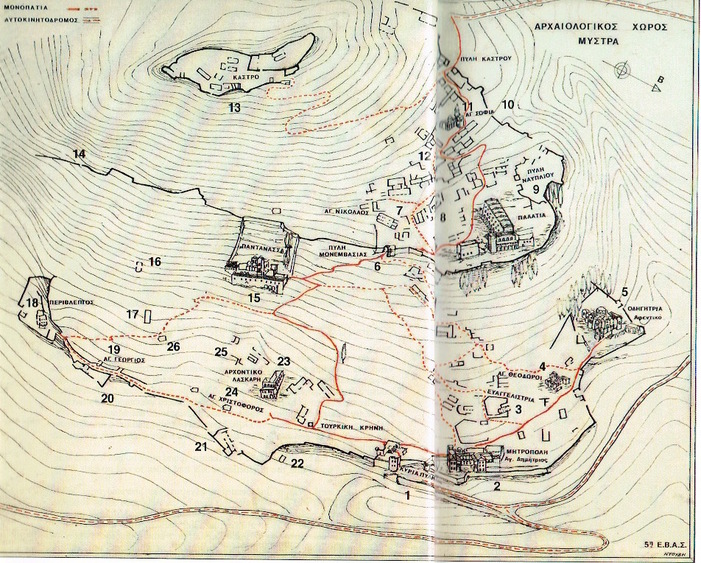

The entire Mystras site is mapped out in this charming sketch by G. Millet (1910) and improved by M. Chatzidakis (1981) (from Chatzidakis book, reference above). This stroll through Mystras was a quiet and arduous climb - there were few people, a pleasure when visiting sites in Greece; contemplative in thinking about what it must have been like in the 13th c.; imposing to behold the pure mass of stone and the effort it took to build this city; ethereal to walk amid the beauty of what remains against the quiet spendor of its fauna and flora with the ocassional bleat of a goat; spiritual to venerate the amazing frescos and mosaics that have been so artfully preserved and displayed. At one point trying to catch my breadth after a long climb I stopped and could hear my heartbeat. A Swallowtail butterfly landed on a bush closeby. There is a wonderful book: Andrea Bonetti, Things that crawl, fly and bloom at Mystras.

|

|

1. Main Gate

2. Metropolis (Agios Demetrios) 3. Church of Evangelistria 4. Saints Theodore 5. Church Hodegetria - Aphendiko 6. Monemvasia Gate 7. Church of St. Nikolas 8. Palace of the Despots and central square 9. The Nauplia Gate 10. Upper entrance to citadel 11. Church of St. Sophia 12. The LIttle Palace 13. The Castle 14. The Mavroporta 15. Chuch of Pantanassa 16. Church of Taxiarch 17. House (Phrangopoulos) 18. Church of Peribleptos 19. Church of St. George 20. House (Krevatas 18th c.) 21. Marmara entrance 22. Ai Yannakis 23. House (Lascaris) 24. Church of St. Christopher 25. Ruined house 26. Church of St. Kyriake |